Eye For Film >> Movies >> Portrait Of Jason (1967) Film Review

Portrait Of Jason

Reviewed by: Chris

Shirley Clarke admitted she made films for people who already understood her wavelength. While that cannot be used as an excuse, it does make Portrait Of Jason a challenge. Will you dismiss it as the nauseous ramblings of an aging black homosexual prostitute? Or might you even pronounce it, as revered Swedish director Ingmar Bergman did, "The most fascinating film I've ever seen"?

There are films that you enjoy. And films that stick with you. Ones that make an impression even if it wasn’t a pleasant one. This is maybe one of those. Jason, talking of his own life, couldn’t have put it better. “It only hurts when you think of it. And if you’re real you’ll think of it a long, long time.” I have a limited appetite for gay humour. And an even more limited one for gay humour that isn’t very funny. The same could be said of my interest in the more sordid revelations of a gay prostitute ‘choosing’ to do all manner of things rather than a regular job. But the human tragedy is quite another thing. And the moral tightrope the filmmakers are treading in making the film - pushing a man to the brink of despair - is mesmerising. The techniques, which also question the nature of documentary itself, leave many questions unanswered.

There is affectionate voyeurism that we have all maybe engaged in. When friends get drunk or do silly things. There’s a saying, “God remembers us by our mistakes, not our perfections.” But what of more uncomfortable revelations? Made unwillingly or willingly? Does the sanctimonious label of ‘truth-telling’ justify hurt? Does complicity? Today we are bombarded with Jerry Springer style TV ‘confessions’. We are inured to ‘reality shows’. Michael Barrymore re-living the pain of his private life on Celebrity Big Brother. Werner Herzog documenting a man who thinks he can talk to bears. We secretly enjoy the pain or stupidity of others.

In the late Sixties, documentary filmmaking was enjoying new found freedoms in showing ‘truth’. Hand-held cameras could record fly-on-the-wall action. Viewers could ‘draw their own conclusions’ in movies like Don’t Look Back. European cinéma vérité was persuading audiences of a simple objective truth. One that could just be ‘noticed’. Portrait Of Jason has rightly been described as a journey into a man’s soul. But it mirrors the transformation of voyeurship with the advent of the video. “The very thing that was trying to be hidden is now the thing that is trying to be exposed,” Clarke explained. Where the audience was the watcher, the filmmaker is now the watcher. In Portrait Of Jason, putting something on film changes the dynamic intensity – what was boring in real life becomes fascinating once it is filmed and edited.

Unlike the fly-on-the-wall technique of Don’t Look Back – or even Shirley Clarke’s own biopic of the poet Robert Frost - the filmmaking process in Portrait Of Jason deliberately interacts with the subject. Not to manipulate truth, but to elicit a deeper truth. It has been called ‘self-reflexive documentary.’ The eponymous Jason introduces himself at length, but later contradicts himself, admitting his real name is Aaron Payne. The filmmaking process has become part of the subject matter. How far can identity be uncovered by means of interview? What can be believed?

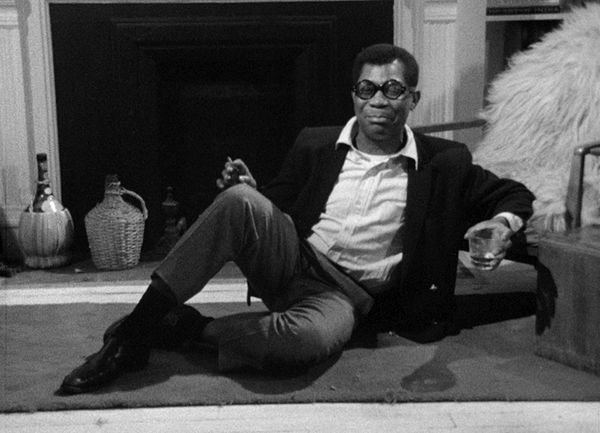

Portrait of Jason is Warholian in its simplicity. A middle-aged black man talks on camera for an hour and three-quarters. But the bite is that although willing, he is obviously not only under the influence of drink and drugs: he is tired and repeatedly gets up to go home. That it has been edited down from 12 hours of footage is testimony to the reality of the camera’s lengthy cross-examination.

Jason Holliday is a remarkable individual. And also a nobody. For him, this film is an opportunity to be immortalised. “It is a nice feeling,” he explains. Something he will always have and treasure.

At the beginning, Jason revels in self-caricature. The fact that he is a drug-user and a prostitute. “I’m a stoned whore!” he boasts with camp exuberance. We learn he grew up with an overbearing father – which he describes with the wit of a stand-up comedian. He makes amusing stories out of his road to homosexuality. He explains how he turned a racist environment to his advantage working as a houseboy. He always wanted to be a stage performer and delights in showing us his material – from Gone With The Wind takes to Carmen. He dons a hat to do an impression of Mae West.

But the ‘evening’ wears on. Jason’s ability to project his misery as something we can laugh at wears thin. He is tired. But he still rises to the call for ‘material’. This, together with the questioning, connects to his desperate side. He wants to show us he is proud of his life. We are drawn in but at the same time maybe not wanting to know. “How did you get the 75 cents for the bed?”

When Jason breaks down and cries we know we have hit rock bottom. Documentary ‘truth’ by a process of wearing down. But is it fair to do this to any human being?

A confrontation with one of the off-camera interviewers (Carl Lee, Clarke’s collaborator and Jason’s friend) results in an almost Springer–like outtake. I had doubts about being able to listen to these extended monologues but now I am feeling decidedly uncomfortable. What is the point? I hadn’t found many of his gags particularly funny. I couldn’t even accurately decipher all of his slang. I just wanted to wrap the man in a warm coat and put him in a taxi home, to get the sleep he obviously needed.

I leave the auditorium with a bad taste in my mouth. But days later I realise the film has made a deeper impression on me than many I have seen. The insights into racism in the U.S. (“The great problem of our time,” as Shirley Clarke called it) are humbling. Certain phrases stick in my mind. “Are you lonely?” they asked him. “I’m desperate,” he replied, “but I’m cool!” And in spite of the hell he has been through he says he is, “Happy about the whole thing,” when asked about the filming. It was maybe not the immortalisation he expected. But Jason Holliday will certainly never be forgotten. I start to think that Clarke did him a kindness. Then I read how, in a 1983 interview, she had admitted, "I started out that evening with hatred, and there was a part of me that was out to do him in, get back at him, kill him." The sentiment seemed shared by boyfriend Carl Lee, who lashes out at Jason, calling him a "rotten queen." Did my previous judgement hold true? Even if their motives were not as clean as I had given them credit for?

It seems to me that Clarke maybe uses Holliday as a means to an end, even if that end is breaking new ground in filmmaking. The use of dramatic fictional techniques for documentary purpose, in films such as Herzog’s Grizzly Man or Spurlock’s Super Size Me, had not really been invented. Films such as Capturing The Friedmans, many years later, although made with the family’s consent, would expose their subjects to a scrutiny that was not always favourable. Yet elements of the moral uneasiness of that much later documentary are apparent in Portrait Of Jason. In Freidmans, we can justify the intrusion on the bases both of willingness and the possibility that serious harm has been committed. But Jason doesn’t stand accused. Then again, it is one of the earliest films to look at a gay protagonist in an open and sympathetic manner. Nor is he stereotyped or romanticised. But is he self-exploited? Or does the film entrap him? It may be that the benefits outweigh any harm. He forever tells us, "I'll never tell." But evidently needs little encouragement to do so.

Reviewed on: 01 Jul 2008